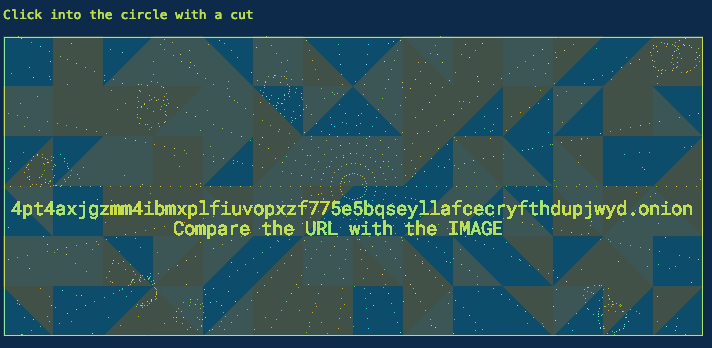

If you’ve ever visited a DNM or looked into how they operate on a technical level, you’ve probably stumbled upon dynamically generated anti-phishing CAPTCHAs. Nowadays they’re commonly utilized to prevent scraping, and more importantly man-in-the-middle phishing attacks targeting the market’s customers.

I’ve always been fascinated of ingenious design of these systems, and followed closely how they’ve evolved over time to combine multiple puzzle-like interactive elements without utilizing any JavaScript. Platforms like Dread are riddled with posts of new users complaining about the difficulty of these CAPTCHAs, but in reality (at least once you get used to solving them) they’re way less frustrating for the end-user compared to mainstream alternatives like reCAPTCHA, hCAPTCHA, or Arkose Labs.

I don’t have any use for anti-phishing protection on my sites, but the way these systems dynamically generate images sparked an idea in my head to implement a similar system to generate randomized banners with my site’s clearweb and hidden service URLs in them. Specifically I was excited of the idea that by rotating the banner with a scheduled task or by adding an endpoint to serve a random banner on every visit, I could freshen up the look of the landing page without utilizing any client-side scripts (or an overkill solution like server-side rendering).

Perlin noise algorithm

After initializing the project, I didn’t have a clue about procedural content generation or its go-to algorithms. Based on the first few searches I quickly figured Perlin noise was exactly what I was looking for, which probably would’ve been clear from the start if I had ever looked into how videogames handle procedural terrain/texture generation or water/wave simulations.

TL;DR Perlin noise works by laying a grid over an image. In this grid, a random gradient vector is placed at each corner where the grid lines meet. For any spot in the image, it then looks at the four nearest gradient vectors and calculates dot products to determine how much each of them influences that spot – either by pushing toward it (positive influence) or away from it (negative influence). Smooth interpolation blends these four corner influences without creating harsh edges, unlike what linear interpolation would produce. For the final product, multiple grids of different sizes (octaves) are typically layered together, with large grids creating broad features and small grids adding fine details.

Implementation

Now that I knew what methodology to utilize, I settled on the following “roadmap” for my project:

- Background generation using go-perlin with a set of custom color gradient themes

- Text overlay with randomly picked positioning and coloring

- Some kind of automated rotation system either from a pool of “active” banners or just a simple scheduled task that’d replace the old banner periodically

Background generation

After looking at some template-like examples and experimenting with the octave scales, I implemented a system utilizing three noise layers: a primary pattern layer scaled to [0.008, 0.023] that establishes the overall flow and structure, a medium detail layer scaled to [0.025, 0.05] that adds intermediate texture variations, and a fine detail layer scaled to [0.06, 0.1] that provides subtle surface complexity. Based on my trial and error this was roughly the sweetspot between enough textural variety to prevent outputting bland backgrounds and preventing visible graining.

For every pixel of the background, I performed the following steps:

// additional distortation (applied with .4 probability) to prevent being too bland

baseX += math.Sin(float64(y)*0.015) * distortionStrength * 200

baseY += math.Cos(float64(x)*0.015) * distortionStrength * 200

// calculated for each (x, y) of all three layers

fx1 := baseX * scale1

fy1 := baseY * scale1

// calculated for each of the three layers which are then combined

noise1 := perlinNoise.Noise2D(fx1, fy1)

// normalized to [0, 1] after being combined with the weights randomized from the aforementioned ranges

noise := min(max((combined+gradientX+gradientY+1)/2, 0), 1)

// used as an input for interpolation to determine the pixel's rgba values

pixelColor := palette.interpolate(noise)

Between calculating the layer-specific floating point noise value and normalizing the final value, the layer-specific noise values must be combined with their respective weights. To be fair, I have no clue on the usefulness of this detail, but I still added alternative blend modes besides the standard linear combination to be applied on an equally random basis.

// standard linear combination

combined = noise1*weight1 + noise2*weight2 + noise3*weight3

// multiplicative blend

combined = (noise1*weight1)*(1+noise2*weight2)*(1+noise3*weight3) - 1

// maximum blend (sharper patterns)

values := []float64{noise1 * weight1, noise2 * weight2, noise3 * weight3}

combined = math.Max(math.Max(values[0], values[1]), values[2])

// turbulence (more chaotic patterns)

combined = math.Abs(noise1)*weight1 + math.Abs(noise2)*weight2 + math.Abs(noise3)*weight3

// randomized gradient with variable direction and strength

gradientX := (float64(x) / float64(config.BannerWidth)) * gradientStrengthX * gradientDirectionX

gradientY := (float64(y) / float64(config.BannerHeight)) * gradientStrengthY * gradientDirectionY

Text overlay setup

The text positioning system employs a two-tiered approach that initially attempts to randomly position each text element within safe boundaries (accounting for text dimensions and outline thickness) without overlapping with previously placed elements, and falls back to placing elements in any of the banner’s corners if the initial placement method falls short:

- For each candidate position, generate a random point within the banner’s boundaries so that the whole textbox fits within the frame.

- Perform a simple overlap check against the bounding boxes of all previously placed texts.

- If no overlap is detected, draw the text there. Otherwise, iterate through steps 1-3 until we’ve run out of attempts or a non-overlapping position is found.

- If no position can be found within the maximum attempts, calculate how much the bounding box would overlap in each of the banner’s four corners and pick the one with the least overlapping area.

Initially I didn’t pay any attention to the order in which these elements were placed, but in hindsight it was quite obvious that placing a drastically larger element, like a multiline hidden service v3 URL, first saves a lot of attempts since the smaller element is more likely to fit into the leftover space than the other way around.

Content serving

When I initially created this tool, I wanted to have it as a separate daemon that’d maintain a pool of n banners while replacing the oldest one of them every 12 hours or so. As my blog’s hosting stack was fully containerized back then, it seemed like the simplest solution to spin up a new Alpine container and connect it to the Nginx container via a volume where the banner pool would reside in.

First I considered using Nginx’s ngx_http_random_index_module, but unfortunately that’d have required using a custom container image instead of the standard one and I didn’t bother going that deep. Instead I wrote a simple shellscript to pick a random banner from the pool, copy it into b.png, and then serve that from a dedicated endpoint.

for site_dir in /banners/*/; do

if [ -d "$site_dir" ]; then

rm -f "$site_dir/b.png"

rb=$(ls $site_dir/*.png | grep -v b.png | shuf -n 1)

if [ -n "$rb" ]; then

cp $rb $site_dir/b.png

chmod 644 $site_dir/b.png

fi

fi

done

location /randban {

root /usr/share/nginx/banners;

# match caching with the rotation frequency

expires 5m;

add_header Cache-Control "public, max-age=300";

try_files /b.png =404;

}

Since then I’ve changed the appearance of the landing page so that I don’t have any use for these banners anymore, but I still occasionally utilize the tool or specific parts of it to generate graphics and such.